PUEBLOS: Masonry and Adobe Communal Housing |

|---|

|

|

|

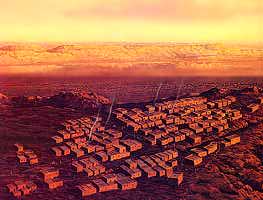

Built of masonry -- squared rocks on rocky mesas and mountains -- or of adobe, a clay mixture, on desert flats where there is little rock, these flat-topped buildings of many rooms, often stacked, are an ancient form of Native housing, in the southwest. Mesa Verde, built by the ancient Anasazi, was abandoned during a long drought in the 13th century, stands in ruins in a mesa cliff cave. It inspired Hopi potter-engineer Al Qoyawayma to make this wonderful pot depicting it. The Anasazi from here (and the large settlements in Chaco Canyon) resettled among the many pueblos along the Rio Grande river. Ancient Anasazi probably are among Qoyawayma's ancestors, some who ultimately settled on the 3 Hopi mesas in Arizona.

As an engineer, and one of the founders, in 1977 of American Indian Science and Engineering Society, Qoyawayma has written about the meaning of science and engineering to native peoples of all nations: "Today, after 16 years of progress, AISES serves the Indian community nationwide. With nearly 100 student chapters, several thousand student, professional and corporate members, pre-college programs, and an annual national leadership training conference, AISES has become one of the strongest groups for youth motivation in the nation. AISES is spreading hope and opportunity throughout Indian country. A new kind of warrior is being trained. "AISES is not interested in producing grist for the competitively driven materialistic corporate and government mills. Emphasis is placed on the realization of a balanced life, balanced in appreciation and knowledge of their culture and their spirituality. Emphasis is placed on the family and communitybuilding. In fact AISES has called itself "The Family". Students are taught by example to pray, to be thankful and have respect for their elders. The spirit is so strong that it is spreading throughout lndian country, into other Indian organizations as well. Perhaps the spirit will spread to society as a whole. We have that hope! " These engineer-warriors are both builders and thinkers, attempting to preserve that which is valuable of the past, and to devise new ways for living in the present and future that will foster cultural survival as well as recovery from centuries of destruction and oppression. This means repairs of damaged structures, many still being lived in, functional in their environments, and providing homes for a still-viable way of life. But there are damaged lands, and damaged lives -- all of which science and engineering can help with, if governed by educated Indian people who have not lost their ancient tribal values, and who are not "grist for materialistic corporate and goverment mills." "And my role as an artist? The role of my art and life as an artist is to glorify God, our creator. As with our ancestors, Native American artists can help interpret through inner spiritual eyes the world and the environment that surrounds us. Artists will help us to see. They will provide a nonverbal record of history. As a potter I work with the precious earth, the living clay. I too have learned that all things are interconnected."

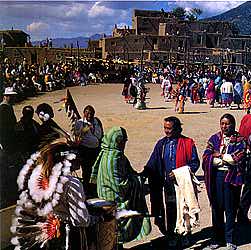

Spiritual life is not lived only in the pueblo and its underground kivas, and dancer's plaza in the Middle. Blue Lake, high in the mountain that shelters the pueblo, has been sacred to the people since time immemorial. In 1906, without consulting the people, the U.S. government took the entire mountain, including Pa whe chal mu, the sacred lake and the 20-mile processional path to it, used only by the villagers for ceremonies at the end of each summer that outsiders are not permitted to attend. For 65 years, the people struggled to get this land and their sacred lake back, refusing a variety of monetary offers, and insisting "It is our church, it is not for sale." These years of sustained, struggle were expensive (especially for the poor people of a pueblo which has no significant resources except driblets of money from tourist visitors). The struggle culminated -- but didn't end -- in 1971, with Congress returning the lake itself and 48,000 surrounding acres to Taos Pueblo. The people are shown celebrating, in 1972 with Taos governor Pa chal ma (Deer Catcher, or Paul Bernal) who devoted his life to the return of Blue Lake shaking hands with visiting tribespeople, a white gift blanket draped over his arm. This victory after three generations for the people of Taos Pueblo has had many important consequences for other Indian land claims, where the people do not want money, but want their sacred land back -- for example, the Lakota people have refused large monetary offers for the taking in violation of treaties of their sacred Black Hills in South Dakota, and particularly want the return of the sacred Bear Butte on the Black Hills, presently a tourist-visited park area. To the present, Taos Pueblo has no running water, sewers, or electricity, in accord with the ancient beliefs that the people are as one with the earth. Ma wha luna, the river that originates in the sacred Blue Lake watershed, runs year-round, supplying life to the surrounding area and to the pueblo village whose center it runs through. Hundreds of thousands of acres of the surrounding mountain and forest land -- which supports the watershed -- was mostly not returned to the pueblo, and is being both logged and grazed by cattle, maintained by wealthy white ranchers. Land returned to the pueblo in 1972 excluded 2,000 acres called Cu tun na (Where the Bears live) that includes a portion of the pilgrimage trail. Many pueblo elders now feel that more education is needed, so young people will learn more about this land, and what it took to get it back, in preparation for succeeding phases of the land claim battle. "We need to emphasize to our young people what it means to stand their ground," says Pien pah (Mountain Cloud or Vince Lujan Sr.), Real Property Officer for the Taos Pueblo. The end of this story about this ancient type of houses emphasizes what Hopi engineer-artist Al Qoyawayma (whose Nation also lives in pueblos on rocky mesas) said at the outset: Indian Nations need more young people with the knowledge and skills of science, but the committments and values of their tribal traditions. You can learn more about the Rio Grande pueblos of New Mexico by clicking the pueblos on the New Mexico reservations map, here. Learn more about Al Qoyawayma's Hopi people (especially their current land struggles mainly with the large, surrounding, Navajo tribe and Peabody Coal) by clicking their reservation on the Arizona reservations map here. |

Acoma, meaning "the place that always existed" in the Keresan language, is commnly called "Sky City" today. It's 357 feet high on the steeply cliffed Acoma Mesa, about 60 miles west of Albuquerque, NM. This 1883 photo shows why it was easy to defend Acoma against enemies. The reservation of Acoma Pueblo today also includes the villages of Acomita and McCartys,

Acoma, meaning "the place that always existed" in the Keresan language, is commnly called "Sky City" today. It's 357 feet high on the steeply cliffed Acoma Mesa, about 60 miles west of Albuquerque, NM. This 1883 photo shows why it was easy to defend Acoma against enemies. The reservation of Acoma Pueblo today also includes the villages of Acomita and McCartys,  where most people live throughout the year. But some people still live in Sky City (which is visited by thousands of tourists who make the steep climb that defeated the pueblo's enemies in historic times. during the summer), as the evening chimney smoke from its ancient stone houses shows. Acoma today has a serious water problem -- an antiquated system of pumps and decaying pipelines -- which they are solving with funds generated by their new casino. Read about it, and more about Acoma Pueblo, [Link gone]

where most people live throughout the year. But some people still live in Sky City (which is visited by thousands of tourists who make the steep climb that defeated the pueblo's enemies in historic times. during the summer), as the evening chimney smoke from its ancient stone houses shows. Acoma today has a serious water problem -- an antiquated system of pumps and decaying pipelines -- which they are solving with funds generated by their new casino. Read about it, and more about Acoma Pueblo, [Link gone] The two adobe pueblo complexes of Tiwa-speaking Taos Pueblo in northern New Mexico, face each other across the small river which runs through the middle of the plaza from the sacred Blue Lake high in the mountain.

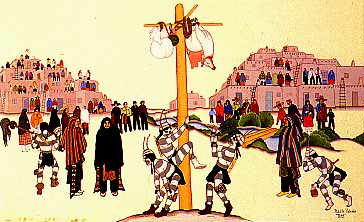

The two adobe pueblo complexes of Tiwa-speaking Taos Pueblo in northern New Mexico, face each other across the small river which runs through the middle of the plaza from the sacred Blue Lake high in the mountain. Koshare clowns try to climb a pole at one of Taos pueblo's sacred dances, painted by famed Santa Clara painter Pablita Velarde in 1947. Divided by the stream from Blue Lake, the two halves of the pueblo form bleachers for the people who have come from their apartments or climbed the many ladders to watch the dancers in the plaza.

Koshare clowns try to climb a pole at one of Taos pueblo's sacred dances, painted by famed Santa Clara painter Pablita Velarde in 1947. Divided by the stream from Blue Lake, the two halves of the pueblo form bleachers for the people who have come from their apartments or climbed the many ladders to watch the dancers in the plaza. Visited by thousands of tourists during the summer, residents of Taos were frequently intruded upon in their apartments. Signs now attempt to keep tourists from climbing up to view the dances or enter the upstairs apartments. Taos pueblo is 5 stories high at the back, stepping down to ground-level at the plaza, called the Middle, facing the stream from the sacred Blue Lake which divides the two halves of the pueblo village.

Visited by thousands of tourists during the summer, residents of Taos were frequently intruded upon in their apartments. Signs now attempt to keep tourists from climbing up to view the dances or enter the upstairs apartments. Taos pueblo is 5 stories high at the back, stepping down to ground-level at the plaza, called the Middle, facing the stream from the sacred Blue Lake which divides the two halves of the pueblo village.