|

|---|

|

|

|

The hogan is a sacred home for the Diné (Navajo) people who practice traditional religion. Every family -- even if they live most of the time in a newer home -- must have the traditional hogan for ceremonies, and to keep themselves in balance. The Blessingway, a sacred sing (or chant) ceremony describes the first hogan. According to Hastíín Roger Hathale, the first hogan was built by Coyote with help from the beavers. First Man, First Woman, Coyote and many others had just emerged from the layered worlds undergound to the place of emergence on this world. Coyote suggested that the first hogan be built, a house for First Man, First Woman, and Talking God, but no one except Coyote (who had already done some travelling and snooping) knew what a hogan was. (Some versions of Blssingway say Talking God made the first hogan.) Coyote got logs and instructions on how to build the hogan from the Beaver People. (Cottonwood trees were already found on this world when the people emerged from below.) The first hogan was the fork-stick hogan frame, a pyramid with 5 triangular faces. The first 2 logs are a fork-tipped log placed to the north and a straight male log to the south. The male log is joined into the female fork at the top, symbolizing a strong partnership between a man and a woman, husband and wife, in their future home. Another fork-tipped log is placed from the west (called "Sundown") Two logs are positioned for the open door frame in the east, two more logs placed over the door to frame the entrance, and a final log goes crosswise at the top of the chimney. This completes the original fork-stick hogan's framework, whose construction is described in the Blessingway sing. This is a male hogan. Beaver told Coyote to sit on the ground facing east, holding his knees in both hands. This demonstrated to everyone that the fork-stick hogan was a model of a human being in this sitting position. The door curtain was made of dawn, so people may rise each morning and meet the dawn light. Precious turquoise, white shell beads, obsidian, jet, and abalone shell were placed on the frame with reed plants -- which had carried the people up to their emergence from the worlds below -- (some versions say the precious stones and shells were buried under the log framework). Songs were sung as it was built, to make it a very holy place. The 5 faces of the hogan were named: morning (east), afternoon, Sunset (west), Darkness (north), Argonite (or jet), and Heat wave. These were used to cover the hogan frame like a tarpaulin. Earth was used to fill in the spaces between the framework logs. The first hogan's original covering brought light of different colors into the hogan as the day went on -- bluish light in the afternoon, yellow light for evening, and darkness at night. When the first hogan was completed, a fire was built inside at its center, and sacred ceremonial items were placed inside. The people who later built fork-stick hogans say that the memory of this first one, with its frame and coverings of precious stones, shells and light, makes the simple log framework, the earth-covered structure shown in the 1890 photo above, a personal world-center home of beauty to those who know the Blessingway description of the first hogan's construction. The memory of that first one lives on in all of them since.

|

|

|

Hexagonal (occasionally octagonal) hogans -- new style -- began to be built in the early 1900's. The main reason was the arrival of the railroad, which brought in large supplies of wooden cross-ties, which could be laid horizontally to form walls of a larger, taller home. It formed the shape of the female hogan, but with so much more room inside, and so much easier to keep clean. Hogans today have one round room, usually about 23 feet in diameter. They might still be used for housing in remote areas, but they are mainly used nowadays for family ceremonies and curings, just as we saw for the isolated tipi and sweat lodge some distance from the Montana Blackfeet home. The door always faces east. Men sit sit on the south side, women the north, visiting dignitaries at the west, facing the door, the place of honor. Upon entering, everyone moves clockwise, imitating the sun's movement. |

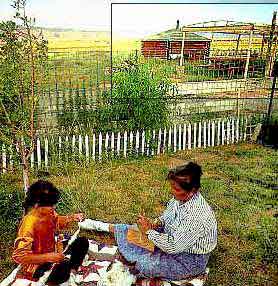

In the back yard of traditional elder Ruth Roessel's more modern home at Round Rock on the Navajo reservation, outlined at right beyond the wire and picket fences, are two traditional structures -- a new-style hexagonal hogan made of logs for ceremonies, and in front of it a shade framework (with a picnic table under it) that is covered with branches for shade for outdoor eating -- and some kinds of wool preparation such as wool dyeing and drying -- in warm weather. In the foreground, inside the yard of the modern house, Nali (grandmother) Ruth teaches her grandaughter, Jaclyn Roessel, how to card and spin wool for weaving, which Jaclyn is starting to learn. In the back yard of traditional elder Ruth Roessel's more modern home at Round Rock on the Navajo reservation, outlined at right beyond the wire and picket fences, are two traditional structures -- a new-style hexagonal hogan made of logs for ceremonies, and in front of it a shade framework (with a picnic table under it) that is covered with branches for shade for outdoor eating -- and some kinds of wool preparation such as wool dyeing and drying -- in warm weather. In the foreground, inside the yard of the modern house, Nali (grandmother) Ruth teaches her grandaughter, Jaclyn Roessel, how to card and spin wool for weaving, which Jaclyn is starting to learn.

|

The prominence of the hogan in Isabel's Yeibichai pictorial rug design reflects the fact that Yeibichai and other ceremonies, healings using sandpaintings, Kinaalda (girl becoming a woman) ceremonies, all require hogans to be properly performed. Since it has been possible to get the wood for the larger, more comfortable hexagonal (or octagonal) hogans , almost no one has built the small, old, earth-covered fork-stick hogans -- the kind whose building is explicitly described in the Blessingway. Hogans are used nowadays almost entirely for ceremonial purposes, though people still live year-round in them while herding sheep in isolated areas. Some buildings such, as the Navajo Community College, shown below, have have been inspired in their shapes by this newer type of hogan. |

|

The Navajo Community College, main campus at Tsaile, AZ, was begun in 1970, in some rooms at Rough Rock Tribal Demonstration School (founded in 1968, and also the first school for Indians to be controlled by Indians). NCC was the first community college to be controlled by tribal people. Others, like the off-reservation boarding schools to which tribal children were taken, were run by the BIA or by religious organizations. Their main purpose was to destroy the Native culture, supplanting it with that of the dominant white society. The college's 6-story modern administration and library building (the Ned A. Hatathli Building) is designed as an octagon (like the tribal council building at Window Rock), to suggest, but not copy, a hogan. In the foreground, in a campus ceremonial area, there is a tipi, and to the right of that, a hogan. The tipi is for ceremonies of the pan-Indian (intertribal) Native American (Peyote) church, to which more than 30,000 reservation Navajos belong. The hogan is for traditional Navajo ceremonies, for the larger group following and reviving Navajo traditions. The Navajo Community College, main campus at Tsaile, AZ, was begun in 1970, in some rooms at Rough Rock Tribal Demonstration School (founded in 1968, and also the first school for Indians to be controlled by Indians). NCC was the first community college to be controlled by tribal people. Others, like the off-reservation boarding schools to which tribal children were taken, were run by the BIA or by religious organizations. Their main purpose was to destroy the Native culture, supplanting it with that of the dominant white society. The college's 6-story modern administration and library building (the Ned A. Hatathli Building) is designed as an octagon (like the tribal council building at Window Rock), to suggest, but not copy, a hogan. In the foreground, in a campus ceremonial area, there is a tipi, and to the right of that, a hogan. The tipi is for ceremonies of the pan-Indian (intertribal) Native American (Peyote) church, to which more than 30,000 reservation Navajos belong. The hogan is for traditional Navajo ceremonies, for the larger group following and reviving Navajo traditions. |

"Bassho" Yazzie is so glad it's Friday from inside the Navajo Community College library in the year 2006. The top panel from this first Tribal Force Native superheroes comic (artist Ryan Huna Smith, mixed-blood Navajo, and writer Jon Proudstar, mixed-blood Yaqui) overviews the NCC campus, where the buildings have (as of 1997) been sited according to Navajo traditional values. Because south is associated with daylight and the knowledge needed to earn a living, this section of the campus houses classrooms for vocational and professional subjects. The library, symbol of sacred knowledge, is located on the north side of the campus, the direction where (in a hogan), the medicine bundle would be stored. The more direct overhead view in the small panel, top right, showing Bassho leaving the library, also shows the octagon shape of the building from above its roof. Visit the real (well, web) Navajo community College main campus (there are 5 satellites) at Tsaile. As with the tipi, which we saw has become both a center of family spiritual life (as shown in the Montana Blackfeet family's tipi and sweat lodge photo), and a symbol of modern Indian pride (as in colorful canvas tipis taken to powwows for camping), the Diné hogan has become a center of spiritual life -- and thus still a home, a home for the spirit -- even if most Diné people now live their everyday lives in more modern-style housing . Hastíín Roger Hathali said "Today, many young people do not observe this part of the Diné culture (building a hogan); therefore many songs and prayers are being forgotten by the Diné families . . . When the fork-stick hogans are built again, the culture may revive. " The shape of the new style 6 or 8-sided hogan has become an inspiration for Navajo-chosen modern buildings such as the college library and tribal council building, created with the most modern materials to build for the future life of the People. See the Navajo Nation's own website. A scholarly (citing many anthropology books) article on the hogan, with sound files pronouncing some Diné words. Visit the Navajo Nation official website and the Nation's official Department of tourism info site. |

The Red Earth Indian Museum (Oklahoma) has a cutaway tabletop model of a fork-stick hogan. The straight male log (south) has its butt end to the front and the door (east) is on the left of the picture here. The straight log fits into the fork-tip of the female log, whose butt end is at the north (to the back of this model). The West (Sunset) log barely shows at the right edge of the cutaway. The doorframe and the two doorframe roof logs are at the left of the pictured model. Continuing the Blessingway first hogan instructions:

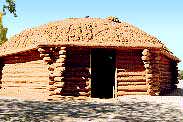

The Red Earth Indian Museum (Oklahoma) has a cutaway tabletop model of a fork-stick hogan. The straight male log (south) has its butt end to the front and the door (east) is on the left of the picture here. The straight log fits into the fork-tip of the female log, whose butt end is at the north (to the back of this model). The West (Sunset) log barely shows at the right edge of the cutaway. The doorframe and the two doorframe roof logs are at the left of the pictured model. Continuing the Blessingway first hogan instructions: To protect a fork-tip hogan against bitter winter cold, when a hogan is built in windy places (such as this Monument Valley one) it might be entirely covered with packed adobe or mud, if it was in a valley where earth or clay is available, hiding the 5-faceted shape of the first or male hogan with thick, winter-protective walls. This round-looking packed-mud femalehogan was constructed by the Navajo Nation, for its Monument Valley parksite, where tourists can photograph and look inside this life-sized model without disturbing people, sacred objects, or hogans abandoned because a death has occurred inside.

To protect a fork-tip hogan against bitter winter cold, when a hogan is built in windy places (such as this Monument Valley one) it might be entirely covered with packed adobe or mud, if it was in a valley where earth or clay is available, hiding the 5-faceted shape of the first or male hogan with thick, winter-protective walls. This round-looking packed-mud femalehogan was constructed by the Navajo Nation, for its Monument Valley parksite, where tourists can photograph and look inside this life-sized model without disturbing people, sacred objects, or hogans abandoned because a death has occurred inside. This sleazy bundle of straws lightly heaped with dirt is supposed to be a hogan. As can be seen from the caption, the authors of this offensive children's Indian culture book Make It Work: North American Indians, a Hands-On Approach to History do not know about the original 5-sided (pentagonal) fork-stick hogan, which their straw heap imitates, nor the more modern (since 1900) hexagonal-octagonal ones discussed below. In supposedly teaching our culture and history by having children make these inaccurate, culturally and environmentally unexplained models, neither cultural significance nor environmental fit are discussed.. Neither history nor culture is learned with these trivial toys. Inauthentic "Indian costumes" as well as inaccurate models with snippets of historical misinformation form a marketing of Native cultures, produced (expensively) in London and aggressively sold to schools in Britain, Canada, and the U.S. This book is an extreme example, but it is also typical of what seems to be a lot of classwork in non-Indian schools that is resulting in teacher-student-parent emails to me about how to build "traditional" housing models. for the offensive, undesirable costume-play-identity, toy-village approach to studying our history -- an approach which also assumes we are either gone or so changed these things no longer have the meaning they in fact still have to Indian people, who are still here. Speaking of hogans in the past tense is not correct. Ignoring the original first hogan -- and that how it was built is part of the Diné Creation Story -- and how that beauty shaped the meaning of later hogans built by later Navajo people, is not correct. Ignoring the spiritual meanings of these ancient ways is always done. There seems to be a great outpouring of what's best described as "Native American Trash Craft" schoolbooks for (bad) multi-cult ed. Personally, I'd rather have them learn something about treaties, sovereignty, and land rights than waste time on this kind of trashcraft, that turns our cultures into sleazy toys.

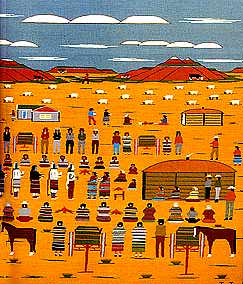

This sleazy bundle of straws lightly heaped with dirt is supposed to be a hogan. As can be seen from the caption, the authors of this offensive children's Indian culture book Make It Work: North American Indians, a Hands-On Approach to History do not know about the original 5-sided (pentagonal) fork-stick hogan, which their straw heap imitates, nor the more modern (since 1900) hexagonal-octagonal ones discussed below. In supposedly teaching our culture and history by having children make these inaccurate, culturally and environmentally unexplained models, neither cultural significance nor environmental fit are discussed.. Neither history nor culture is learned with these trivial toys. Inauthentic "Indian costumes" as well as inaccurate models with snippets of historical misinformation form a marketing of Native cultures, produced (expensively) in London and aggressively sold to schools in Britain, Canada, and the U.S. This book is an extreme example, but it is also typical of what seems to be a lot of classwork in non-Indian schools that is resulting in teacher-student-parent emails to me about how to build "traditional" housing models. for the offensive, undesirable costume-play-identity, toy-village approach to studying our history -- an approach which also assumes we are either gone or so changed these things no longer have the meaning they in fact still have to Indian people, who are still here. Speaking of hogans in the past tense is not correct. Ignoring the original first hogan -- and that how it was built is part of the Diné Creation Story -- and how that beauty shaped the meaning of later hogans built by later Navajo people, is not correct. Ignoring the spiritual meanings of these ancient ways is always done. There seems to be a great outpouring of what's best described as "Native American Trash Craft" schoolbooks for (bad) multi-cult ed. Personally, I'd rather have them learn something about treaties, sovereignty, and land rights than waste time on this kind of trashcraft, that turns our cultures into sleazy toys. This is the right half of a large pictorial-style rug, woven in 1984 by traditional Navajo elder Isabel John, of Many Farms on the reservation. She pictures the 9th day of a Yeibichai healing ceremony. Some of the dancers are seen in the middle, heading toward the healing place, the hogan at the right foreground. Another hogan, and a small modern house, are visible in the background. There are many spectators (and sheep), and in the foreground are wagons and horses of those who have come for the ceremony. (Today it will be mostly pickups.) The mountains of Canyon de Chelly (visible from Isabel's house) line the background. Between them are the flat-topped mesas of Round Rock (where Ruth Roessel and her husband live).

This is the right half of a large pictorial-style rug, woven in 1984 by traditional Navajo elder Isabel John, of Many Farms on the reservation. She pictures the 9th day of a Yeibichai healing ceremony. Some of the dancers are seen in the middle, heading toward the healing place, the hogan at the right foreground. Another hogan, and a small modern house, are visible in the background. There are many spectators (and sheep), and in the foreground are wagons and horses of those who have come for the ceremony. (Today it will be mostly pickups.) The mountains of Canyon de Chelly (visible from Isabel's house) line the background. Between them are the flat-topped mesas of Round Rock (where Ruth Roessel and her husband live).  In "Blessings of Dawn," Navajo artist Mark Silversmith perfectly conveys the dawn at a winter hogan, where the sheepherder's family -- including baby on mother's back -- have come out of their cosy hogan to sing to the dawn, with a fire getting started on the fresh snow. The sheepherder will no doubt eat, saddle up, and be off to tend the sheep who may be in a close or several distant pens -- often built by fencing a blind canyon -- for the winter. It looks as if their hogan might be located in Canyon de Chelley. It's perhaps somewhat lonely there, and isolated by poor or no roads, mostly cut off to vehicles in snowy winter. But this painting shows why "In Beauty All Around Us" has such a strong hold and deep roots within Navajo culture, and how perfectly a hogan fits in to the awesome world there.

In "Blessings of Dawn," Navajo artist Mark Silversmith perfectly conveys the dawn at a winter hogan, where the sheepherder's family -- including baby on mother's back -- have come out of their cosy hogan to sing to the dawn, with a fire getting started on the fresh snow. The sheepherder will no doubt eat, saddle up, and be off to tend the sheep who may be in a close or several distant pens -- often built by fencing a blind canyon -- for the winter. It looks as if their hogan might be located in Canyon de Chelley. It's perhaps somewhat lonely there, and isolated by poor or no roads, mostly cut off to vehicles in snowy winter. But this painting shows why "In Beauty All Around Us" has such a strong hold and deep roots within Navajo culture, and how perfectly a hogan fits in to the awesome world there.